[ad_1]

Dubai: Gulf countries, especially Saudi Arabia and the UAE, have been praised by WFP regional representatives and expectant mothers for “saving and continuing to save lives through the distribution of nutritious food to children, mothers and nursing mothers”. “

Mageed Yahia, WFP Regional Representative in the Gulf Cooperation Council, appeared on the “Frankly” Arab News weekly current affairs talk show, citing war-torn Yemen, Saudi Arabia and the UAE in 2018 “to work together to save the world” our plan” and prevent hunger.

“The biggest impact of this donation was to avoid famine, to provide ($1) million to UN agencies operating in Yemen. The Saudi contribution has continued since then, and continues to this day. Likewise, doing so The impact is to save lives.”

Yahia’s remarks appeared to contradict comments made by WFP executive director David Beasley during a recent visit to Iceland, where he publicly denounced Gulf states and China for “failure to step up” in their fight against the global food crisis.

The official United Nations website quoted Beasley as telling Icelandic TV that Beasley claimed that “the Gulf states that currently have huge oil profits” “have not stepped up their efforts”: “Iceland is not a big country, but it is surpassing its weight. A good example for the country.”

Beasley’s description of the two Gulf countries also runs counter to WFP’s own 2021 Global Contribution Summary (as of June 21, 2022), which shows Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates as the seventh and twelfth largest, respectively. Donor country. In fact, on a per capita basis, these two states are the two largest donors to the World Food Programme globally.

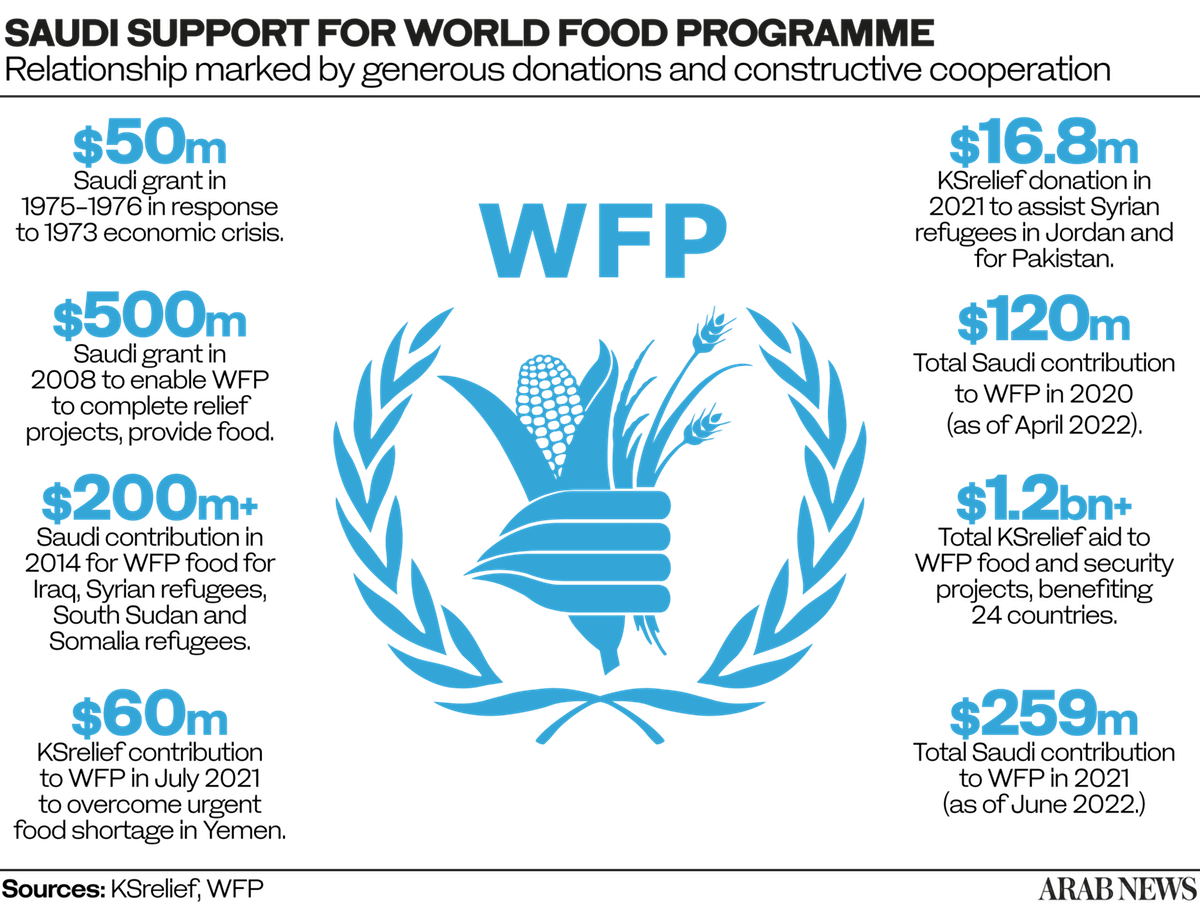

Just last November, the World Food Programme welcomed a “timely and generous donation” of $16.8 million from the King Salman Center for Humanitarian Aid and Relief (KSrelief) of Saudi Arabia to help Syrian refugees in Jordan and support the nutrition of Pakistani women and children plan.

Saudi Arabia’s contribution comes as the World Food Programme struggles to secure funding to continue supporting some 465,000 vulnerable refugees in Jordan, most of them from Syria, and more than 66,000 of Pakistan’s most vulnerable children and women.

Yahia acknowledged the multifaceted benefits of the Gulf through WFP aid to Yemen. “The impact of this is that we keep people there alive,” he said.

“Certainly, the Saudi contribution helps us on the life-saving agenda, but also on the nutrition agenda when it comes to providing specialized nutritious food for children, mothers, nursing mothers and pregnant mothers. Because if you don’t do that today, You’re going to have a negative impact on that tomorrow, (in terms of) the school meals we provide.

He added: “We provide school meals in both the north and the south. This is an ongoing development activity that we are doing. What matters is what the Saudis and Emiratis are doing with us in Yemen to help keep people alive, save lives their lives and (allowed to continue their education).

“It’s very important for the kids there.”

Asked how many lives might be affected by the joint Saudi-UAE aid support, Yahia said: “We’re talking about 40 million people in Yemen. That could be half the population, or more than half the population.”

Global food prices rose rapidly earlier this year as the war in Ukraine disrupted the supply and distribution of grain and fertilizer. This comes on the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic, exposing the fragility of global supply chains.

As a result, many observers have concluded that it is highly unlikely that the United Nations will achieve the Sustainable Development Goal of ending hunger by the end of the century. Yahia still holds out hope.

“First of all, the good news is that zero hunger by 2030 is possible. If the world comes together, it is doable. If there is political will, we can do it. But for the past five years, we have been backwards,” he said.

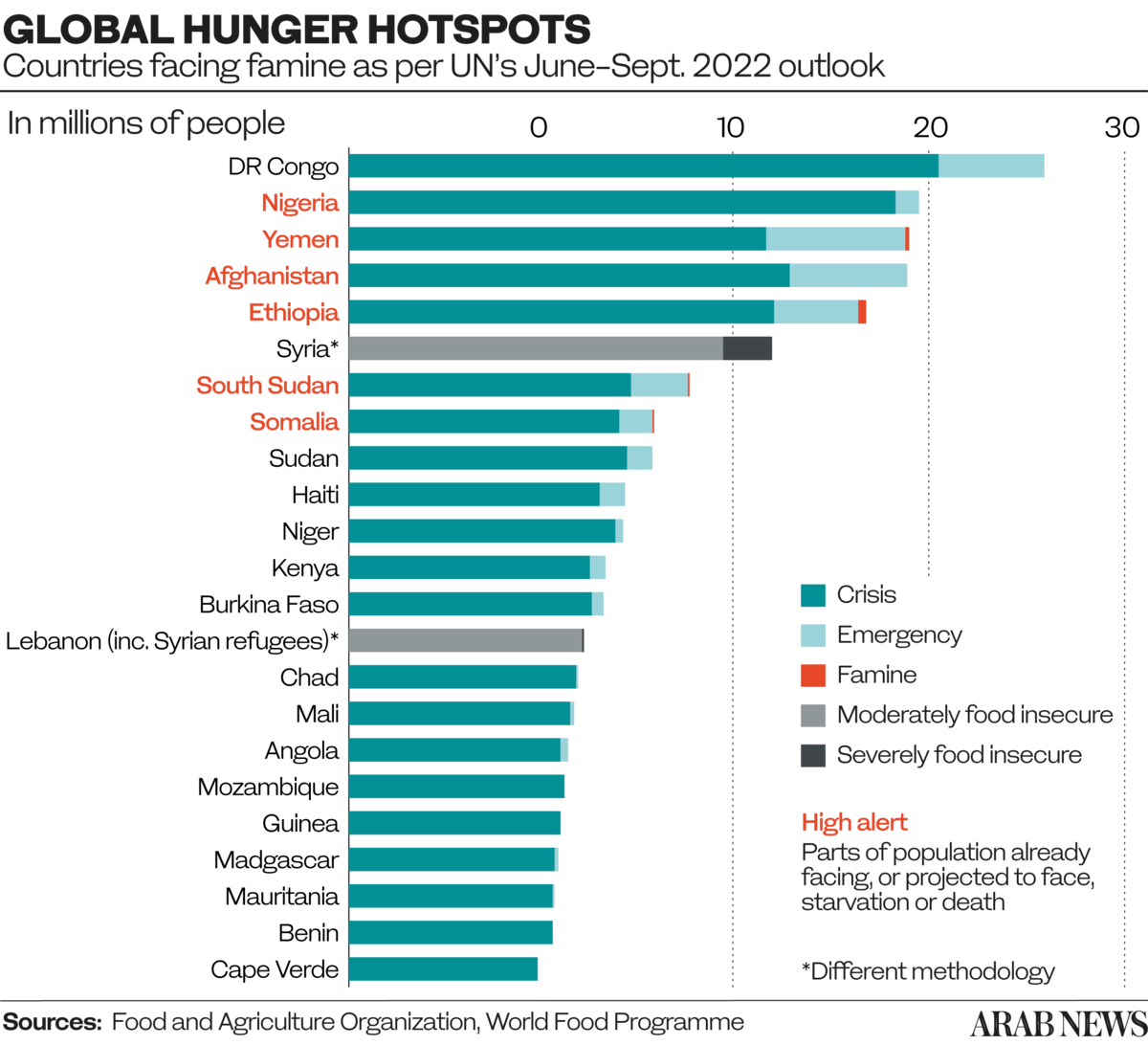

“We saw good progress in 2015, when the number of hungry people decreased, but then started to increase. Conflict is a major driver of hunger around the world. Now we see it in Yemen, we are seeing it in Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan and the Sah le see it.

“The second is climate. Food production is very dependent on climate. So if there is any change there, food production is a problem. That’s what is happening in the Horn of Africa right now, in Somalia, there are about 3 to 4 million People have been displaced by drought.”

Yahia takes pains to explain a conundrum of the global food crisis: “In many cases, hunger is not the result of scarcity, but of affordability. Food is everywhere. The world produces more than it consumes. But in some communities, 800 million people , can’t afford this kind of food.”

According to the regional director, in the Middle East and North African countries that rely heavily on imported food and fertilizers — especially in crisis-hit countries such as Lebanon, Syria and Yemen — the rising cost of these commodities is contributing to hunger and malnutrition.

“You look at the currency devaluation in Lebanon. It’s huge. You look at inflation — food prices are inflated there,” Yahia said. “Lebanon itself is heavily dependent on food imports. At the same time, Lebanon hosts a million Syrian refugees. So all these things come together.”

In Yemen’s case, the distribution of aid is also regularly disrupted by the Iran-backed Houthi militias that control large swathes of the country, including the capital, Sanaa. Reaching vulnerable groups is half the battle, Yahia said.

“As in any conflict, one of the main issues we face when working in conflict zones is reaching people,” he said. “Certainly, it may take 50 percent of our efforts to negotiate access to these populations.

“The second is the number of people who depend on us for food aid. Now we have made a very difficult decision in Yemen by reducing food rations because of funding, because of the long-standing conflict.”

He warned that the reduction in the amount of food the WFP was able to distribute in Yemen was also a result of the reduction in the amount of financial assistance provided by donor countries, as well as the size of the huge needs in several crisis areas around the world. .

“This is mainly due to the protracted nature of the crisis and the fact that crises emerging in different parts of the world could compete with the situation in Yemen,” Yahia said. “But, at the end of the day, we need to make the headlines in Yemen, Syria, South Sudan, all these places, so people don’t forget the situation there.”

One way WFP aims to address supply chain disruptions, alleviate funding shortfalls and improve food accessibility and affordability is to encourage production closer to the point of demand.

“Eighty percent of Africa’s food is produced by smallholder farmers, and unfortunately, some of them end up being the beneficiaries of our aid,” he said. “Why? Because they lose, because they don’t have access to the market. There is no logistical supply chain, there are insufficient storage facilities. So more than half of their harvest is lost.”

To support local farmers, WFP relies on donor countries. However, according to Yahia, with multiple overlapping crises plaguing the vast developing world, the agency lacks the funding it needs to support existing projects.

“We need an additional $9 billion because our forecast for 2022 is $24 billion,” he said. “We’ve raised about $9 billion so far. We know we’re not going to meet our expectations, but if we don’t get it, we’re going to need more next year as the availability crisis looms.

Yahia added: “In the short term, you need to help these communities. You need to save their lives. Unfortunately, because of the conflict, because of the climate, this poses a real threat to the overall food security of the economy, and the numbers continue increase.”

[ad_2]

Source link