[ad_1]

Mahsa Amini’s death in Iranian police custody ignites a nation of anger and discontent

Dubai: Since the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini at the hands of the ethics police, protests have spread to almost all of Iran’s 31 provinces and cities. On 13 September, Amini was arrested by a Moral Police (Gasht-e Ershad) patrol at Tehran metro station for allegedly violating the Islamic Republic’s strict dress code.

She was hospitalized after her arrest, fell into a coma, and died three days later. Iranian authorities insist she died of a heart attack. Her family said she had no previous heart disease.

Her death sparked outrage in a country brimming with anger over a long list of grievances and wide-ranging socioeconomic issues.

Iranian women, fed up with the high-handedness of the moral police, have been posting videos of themselves cutting their hair online in support of Amini. Protesters who took to the streets have been chanting “death to the moral police” and “women, life, freedom”.

During the protests, female demonstrators can be seen taking off their headscarves, burning them and dancing in the streets. State police have been tear-gassing protesters, while IRGC volunteers have been beating them. At least 41 people have died so far.

“The internet in Tehran has been cut off. I can’t reach my family, but every now and then they get news,” an Iranian man who fled to the United States during the Islamic revolution told Arab News.

Mahdi, who did not want to give his full name, added: “We hope the government will give in this time. This is the largest demonstration since the revolution. We are proud of what is happening in Iran.”

Karim Sajdadpour, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, wrote in The Washington Post that the protests against the killing of Amin were “led by the nation’s granddaughter against the grandfather who ruled their country for more than four decades.”

Since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the country’s Sharia law has required women to wear headscarves and loose clothing in public. Those who do not follow the code will be fined or imprisoned.

Iranian authorities require women to dress appropriately, and a campaign against “incorrect” wearing of mandatory clothing began shortly after the revolution, which ended a campaign under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. The free era of free female seamstresses. During the king’s reign, his wife Farah, who often wore suits, was held up as a model for modern women.

Photos of protesters destroying a portrait of the Iranian leader in the northern city of Surrey are just one of the many symbols of anti-government sentiment that has emerged from Iran over the past week. (AFP)

By 1981, women were banned from showing their arms in public. In 1983, the Iranian parliament decided that women who did not cover their hair in public would be punished with 74 lashes. Recently, it increased the maximum 60-day jail sentence.

Restrictions have continued to evolve, and since 1979, women’s dress codes have been enforced to varying degrees, depending on which president is in office. Gasht-e Ershad was formed to enforce a dress code after the ultra-conservative Tehran mayor Mahmoud Ahmadinejad became president in 2005.

Restrictions have eased somewhat during the presidency of Hassan Rouhani, who is considered relatively moderate. After Rouhani accused the ethics police of being aggressive, the head of the force announced in 2017 that women would no longer be arrested for violating the code of modesty.

However, the rule of President Ibrahim Raisi appears to have reinvigorated the moral police. In August, Raisi signed a decree to enforce stricter rules requiring women to wear headscarves at all times in public.

In a speech to the UN General Assembly last week, Lacey sought to deflect blame for the Iranian protests by pointing to Canada’s treatment of indigenous peoples, and accused the West of applying double standards on human rights.

It gives me goosebumps when I see how women fight against evil regimes that never shy away from genocide.

Mahdi who fled to America during Islamic revolution

Meanwhile, the Rice administration is seeking some form of assurance that if a future U.S. president rescinds the 2015 nuclear deal, there will be no disruption to Western companies lifting tough sanctions and resuming business activity. Iranian officials have also disputed the IAEA’s concerns about illegal nuclear material found at three sites and want the IAEA investigation to end.

Protests in Iran are not new. In 2009, the Green Movement protested over what was considered a fraudulent election result. In 2019, there were demonstrations about soaring fuel prices and deteriorating living conditions and basic needs.

This year’s protests are different, they are feminist in nature. Firuzeh Mahmoudi, executive director of the human rights NGO Unite for Iran, said the country saw pictures of women collectively removing their headscarves, burning police cars and tearing up Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the country’s top leader. Unprecedented.

It is also unprecedented to see men chanting “We will stand by our sisters and women, life, freedom”.

“Through social media, mobile apps, blogs and websites, Iranian women are actively participating in public discourse and exercising their civil rights,” Mahmoudi said. “Luckily for the growing feminist movement, patriarchal and misogynistic governments have yet to figure out how to fully censor and control the internet.”

Protests against the death of Massa Amini have erupted across Iran and among the diaspora living around the world. (AFP)

Masih Alinejad, an Iranian political activist who has been in exile in the United States since 2009, said she has received many messages from Iranian women. They have been sharing with her their frustrations, videos of protests, and their farewells to their parents, which they think may be the last.

Alinejad, who said she could feel their anger through their messages, said the hijab was a way for the government to control women and society, adding that “their hair and their identities have been taken hostage.”

Many Iranian male celebrities also expressed support for the protests and women. Toomaj Salehi, a dissident rapper who was arrested earlier this year for his lyrics about regime change and socio-political issues, posted a video of himself walking down the street saying: “My No tears, it’s blood, it’s anger. The end is near, history repeats itself. Be afraid of us, stand back, know you’re done.”

For its part, the film industry issued a statement Saturday calling on the military to lay down its arms and “return to the arms of the nation.”

Some famous actresses have taken off their headscarves in support of the movement and protests. Iranian Culture Minister Mohammad Mehdi Esmaili said actresses who expressed support online and took off their headscarves could no longer pursue their careers.

In a tweet on Saturday, Sajdadpour said: “To understand the protests in Iran, combine images of young modern women (Mahsa Amini, Ghazale Celavi, Hanane Kia, Mahsa Mogoi) killed in Iran last week with the country’s ruling elite , almost all very traditional older men.”

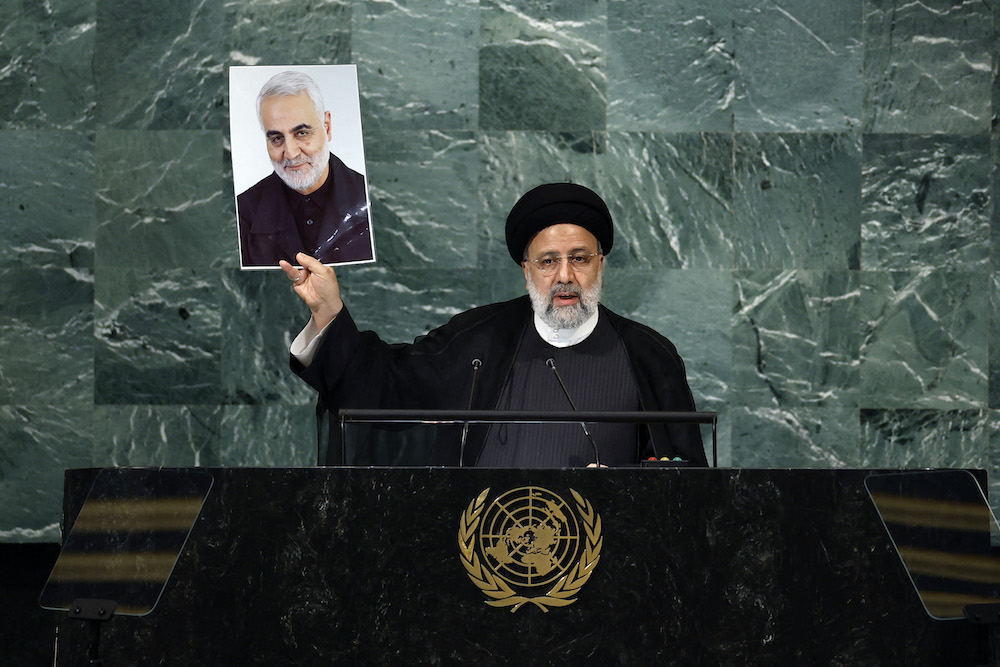

Iranian President Ibrahim Raisi holds up a photo of General Qassem Soleimani, the Quds Force commander killed in a U.S. attack, as he addresses the 77th session of the United Nations General Assembly. (AFP)

Iranian authorities shut down mobile internet connections, disrupting WhatsApp and Instagram services. In Iranian state media, ISNA Communications Minister Issa Zarepour defended the conduct of “national security” and said it was unclear how long the blockade of social media platforms and WhatsApp would last, as it was implemented for “security purposes” and with Discussions about recent events. “

However, Mahsa Alimardani, a scholar at the Oxford Internet Institute who studies internet shutdowns and controls in Iran, said authorities were targeting these platforms because they were “the information and communications lifeline that kept the protests going”.

On Twitter, the hashtag #MahsaAmini in Persian has surpassed 30 million posts.

“Everyone in Iran knows that the authorities will crack down on protesters and kill them,” Mahdi, an Iranian based in the United States, told Arab News.

“It’s pretty much their targeting exercise. It gives me goosebumps when I see how the women out there stand up against a brutal and vicious regime that never shy away from genocide to maintain its power. Doing what they’re doing takes A certain courage.”

Looking to the future with hope, he said: “The flames have been lit and we are not the type to back down.”

[ad_2]

Source link